The Scramble for a Bed: Decoding the Refuges of the Tour du Mont Blanc

The Tour du Mont Blanc is an alpine masterpiece, but its refuges operate by their own ancient rules. Beyond the 170km loop lies a world of "boot room" etiquette, booking scrambles, and communal magic. This guide demystifies the logistics of the TMB, ensuring your journey is as smooth as the mountain air.

The Tour du Mont Blanc is perhaps the world’s most famous walk, and for good reason. It is a 170-kilometre loop that dances through France, Italy, and Switzerland, offering views of the Mont Blanc massif that stay with you long after you’ve returned home. But while the mountains are timeless, the way we experience them has changed.

In decades past, you could pack a rucksack and simply follow the trail, trusting that a mountain hut would have a spare mattress and a bowl of soup waiting. Today, the TMB is a different beast. It is often an organised, and ‒ at times ‒ logistically daunting journey. To walk the TMB now is to participate in an ancient tradition of alpine hospitality that has been retrofitted for the digital age. If you are planning to set foot on this storied path, this article will help you navigate the "invisible" side of the trek: the bookings, the social graces, and the practicalities of living in a mountain refuge.

The Modern Alpine Scramble: Booking Your Bed

Planning the TMB has become a bit like trying to secure tickets for a major music festival ‒ only this "festival" lasts ten days and stretches across three different countries. The days of simply turning up and finding a bed are, unfortunately, largely behind us. You can still find a sense of spontaneity if you are willing to wild camp, carrying your own shelter and stove through the elements. However, for the vast majority of us, the draw of the TMB is that unique blend of rugged adventure by day and a warm bed and hot meal by night.

While the trail’s popularity has soared, the mountain infrastructure has remained largely the same. These refuges have stood for decades ‒ sometimes centuries ‒ and strict alpine regulations mean few new ones are being built. With supply frozen in time and demand reaching an all-time high, "scarcity" is the word of the day. For those of us who value a bit of comfort after a long climb, the dormitory bed has become the most sought-after prize in the Alps.

The Autumn Scramble: A Logistical Jigsaw

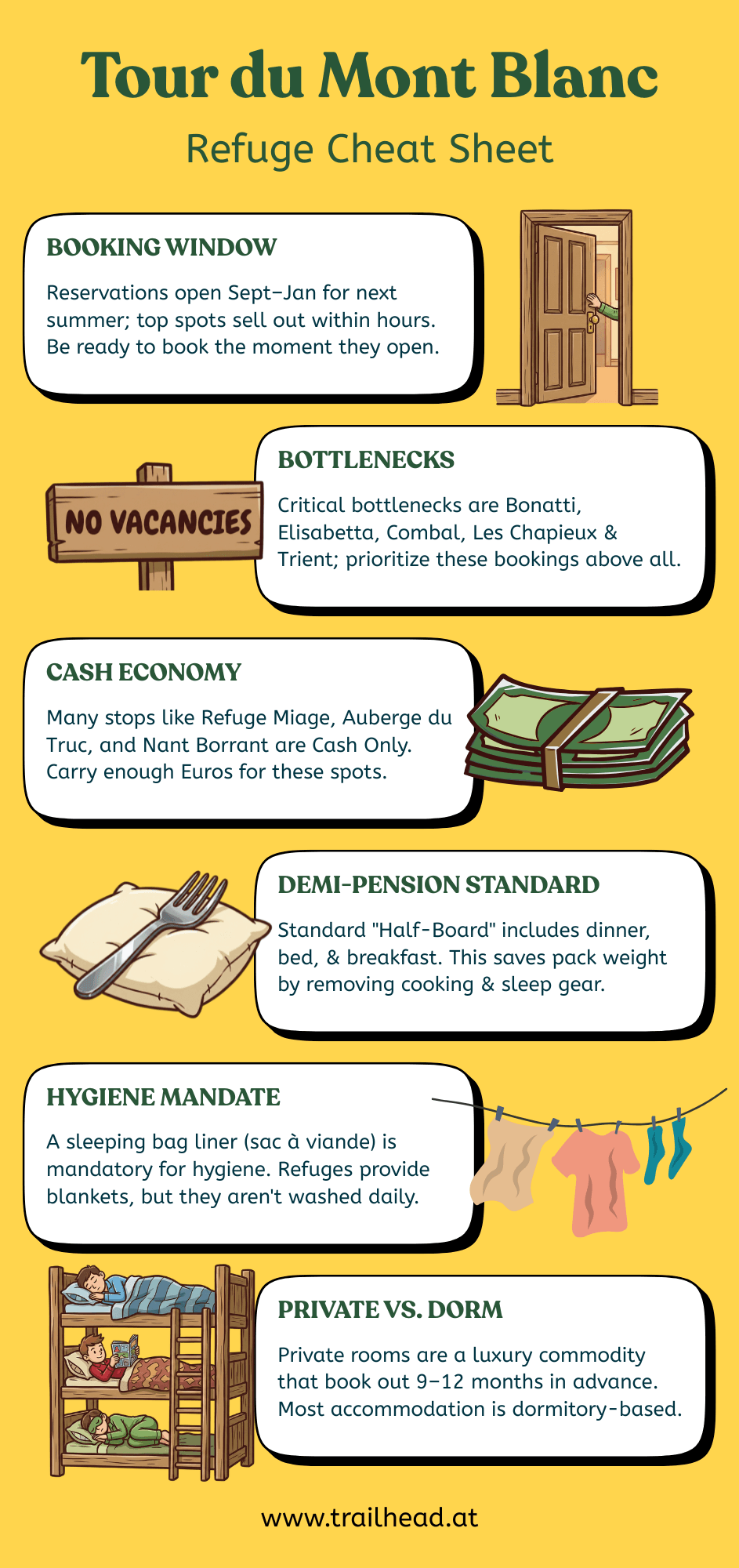

The first thing to understand is the timeline. Planningfor your summer trek doesn’t start in the spring; it begins in the autumn of the preceding year. This "October Rush" has become a defining characteristic of the TMB experience, driven by an intense global demand that far outstrips the fixed number of beds available in the high mountains.

Unlike a standard hotel booking, where you might expect a uniform system, the TMB is a patchwork of independent operators. The rush is intensified by the fact that these establishments operate on staggered schedules. You might find your French refuges opening for reservations in early October, only to discover that the Italian rifugi won’t accept inquiries until November, and the Swiss gîtes wait until the New Year.

This lack of synchronisation turns the booking process into a complex logistical jigsaw. It requires constant monitoring and a high degree of administrative agility. Hikers often find themselves in a frantic period of coordination ‒ sending direct emails, filling out manual web forms, and checking multiple sites daily ‒ all while trying to ensure their chosen dates line up across three different borders.

The lesson here is simple: be early and be flexible. The "rush" is a product of thousands of hikers all trying to solve the same puzzle at once. If you are late to this autumnal scramble, you may find the circuit’s core nodes fully committed. This often forces travellers to stay in the larger valley towns and rely on bus transfers to reach the trail each morning. While these towns offer their own charms, missing out on the high-altitude stays means missing the quiet magic of the alpine dusk ‒ a sacrifice few hikers want to make.

The Myth of the Private Room

We all value our privacy, but on the TMB, a private twin room is a rare and precious jewel. Most refuges are built around the dormitory. These can range from small rooms of four to vast sleeping platforms where twenty people lie side-by-side.

If you absolutely must have a private room, you need to book 9 to 12 months ahead, and even then you will have to make significant changes to standard route. If private rooms is what you are after, check out our TMB accommodation map, and switch 'Private rooms available' to see all the options. However, dorms is part of the trail's charm ‒ the shared rustle of sleeping bags and the collective "Alpine Start" at dawn ‒ but it requires a certain spirit of camaraderie.

Navigating the Bottlenecks

Some of the TMB sections are "choke points." These are the places where the trail’s capacity is at its lowest, and the demand is at its highest. When planning your itinerary, it is wise to secure these "bottleneck" stays first.

The Les Chapieux Crisis

The most famous bottleneck is the stage between Les Contamines and the Italian border. After a long climb over the Col du Bonhomme, you drop into a tiny hamlet called Les Chapieux. There are very few beds here ‒ primarily at the Auberge Reffuge Nova, Les Chambres du Soleil and the Refuge des Mottets a bit further up the valley. If these are full, you are in a bit of a pickle. You may have to take a shuttle down to a town like Bourg Saint-Maurice, which takes you away from the heart of the mountains. Securing a bed in Les Chapieux is the "linchpin" of a successful TMB itinerary.

The Italian Jewels: Bonatti and Elisabetta

Once you cross into Italy, the landscape changes, becoming more jagged and dramatic. Two refuges here are legendary: Rifugio Elisabetta and Rifugio Bonatti.

Elisabetta sits at the head of the Val Veny, looking out over the moving ice of the Miage Glacier. Bonatti is often cited as the best hut on the entire trail, famous for its incredible food and its view of the "back side" of Mont Blanc.

Because of their reputations, these huts sell out almost instantly. If you can’t get into Bonatti, don’t despair; the Italian town of Courmayeur is a wonderful place to spend a night, offering a bit of Italian "dolce vita" before you head back into the wild. Alternatively, Chalet Val Ferret and Rifugio Elena are other options further down the trail.

The Swiss Constraint: Trient

As the trail winds into Switzerland, you encounter another significant hurdle in the village of Trient. While there are a few options, such as Refuge Le Peuty, the Auberge du Mont Blanc, La Grande Ourse, and the Hotel de La Forclaz just up the hill, they are often overwhelmed by the sheer number of hikers descending from the Champex-Lac stage.

When these local beds are full, hikers are often forced to take a bus down to the larger valley town of Martigny. While Martigny is a lovely historic town, the commute back up to the trail the following morning can feel like a chore. Securing your spot in Trient early ensures you stay in the high-mountain atmosphere for the duration of the Swiss leg.

![]()

The Art of the Alpine Refuge

Stepping into a refuge for the first time can be a bit overwhelming. There is a specific rhythm to life here—a set of unwritten rules that keep things running smoothly.

The Boot Room (The Local à Chaussures)

The most important rule of alpine life is: no boots inside. As soon as you arrive, you will be directed to a boot room. Here, you leave your muddy, heavy hiking boots. This isn't just about cleanliness; it’s a crucial measure to prevent bedbugs from entering the sleeping quarters.

Most refuges provide a communal basket of "Crocs" or plastic clogs. While they aren't the height of fashion, they are a godsend for tired feet. However, if the idea of shared footwear makes you uneasy, do pack a pair of lightweight flip-flops or slippers. Your feet will thank you.

The Sleeping Bag Liner (Sac à Viande)

In a mountain hut, you are provided with a mattress, a pillow, and a heavy wool blanket or duvet. Because washing these blankets daily is impossible at 2,500 metres, you are required to bring a silk or cotton liner, known as a sac à viande.

It is a simple piece of etiquette: the liner protects the bedding from you, and you from the bedding. Some huts will actually refuse to let you sleep unless you have one (though they usually have them for sale at the desk for those who forgot).

The "Demi-Pension" Way of Life

Most hikers stay on a demi-pension (half-board) basis. This is the heartbeat of the TMB. It includes your bed, dinner, and breakfast. Dinner is the highlight of the day. It usually happens around 6:30 or 7:00 PM and is a communal affair. You will be seated at long tables with hikers from all over the world. There are no menus; you eat what the mountain cooks have prepared. A typical meal starts with a hearty soup, followed by a carbohydrate-heavy main—perhaps a mountain of polenta with sausages, or a tartiflette (a glorious French concoction of potatoes, cream, and Reblochon cheese). It is simple, warming, and designed to fuel you for the next 1,000-metre climb.

Practical Realities: Money, Power, and Water

The TMB crosses three of the wealthiest countries in the world, yet in the high mountains, you are back to basics.

The Cash Mandate

It is a common mistake to assume that "everywhere takes card" in 2026. In the Alps, satellite signals for card machines are notoriously fickle. If the clouds roll in, the internet often rolls out. Many refuges ‒ especially the remote ones like Refuge de Miage or Refuge des Mottets ‒ remain strictly cash-only. Even in the larger huts, they may only accept cards for amounts over €20. We recommend carrying around €500 per person in cash. While you’ll spend Euros in France and Italy, Switzerland prefers the Swiss Franc (CHF). Most Swiss huts will take Euros, but you’ll get a poor exchange rate and change back in Francs. It's a bit of a "currency soup," but that’s the charm of a tri-national trek.

Electricity and Connectivity

Don't expect to spend your evenings scrolling through social media. Power is a precious resource, often generated by solar panels or small turbines.

- Charging: There might be one charging station for 60 people. It’s better to bring a good-quality power bank (10,000mAh is usually enough) and charge that when you can, rather than relying on finding a spare socket for your phone.

- Signal: Many valleys are "dead zones." Embrace the silence. It’s one of the few places left where you can truly be "off the grid" for a few days.

The Luxury of a Hot Shower

Water in the Alps is abundant, but hot water is a luxury. Most refuges use a "token" (or jeton) system. You pay a few Euros for a token that gives you exactly three to five minutes of hot water. It encourages you to be quick and mindful. In particularly dry years, or at very high-altitude huts, showers might be closed entirely to conserve water for cooking and drinking.

The Alpine Start: A Morning Ritual

The "Alpine Start" is a phrase you’ll hear often. It refers to the tradition of waking up before the sun to get over the high passes before the midday heat (or the afternoon thunderstorms) rolls in.

Breakfast is served early ‒ usually between 6:30 and 7:30 AM. It is a functional meal: coffee (usually served in a bowl, French-style), bread, jam, and perhaps some cereal. By 8:30 AM, the refuge is usually empty, as the staff begin the monumental task of cleaning the dorms for the next 80 hikers arriving that afternoon.

This rhythm ‒ early up, long walk, communal dinner, early to bed ‒ is incredibly grounding. After three or four days, the "real world" starts to feel very far away.

A Note on Packing and Health

The beauty of the refuge system is that you don't need to carry a tent, a stove, or food. This means your pack should be significantly lighter than a traditional trekking pack.

Aim for a rucksack between 30 and 40 litres. If your pack weighs more than 10kg, you’ve probably packed too much. The biggest "weight" on the TMB isn't the physical load; it’s the strain on your knees during the long descents. Keeping your pack light allows you to enjoy the views rather than staring at your boots.

Thermal regulation is also key. Even in the height of summer, the temperature can drop to near freezing at night. However, inside the dorms, it can get quite warm due to the number of people. Lightweight, breathable base layers are your best friend for sleeping.

The "Refuge Kit": A Tactical Guide to Comfort

To navigate this environment gracefully, your packing strategy needs a dedicated "Refuge Kit." Since you will be leaving your rucksack in a dedicated area or at the foot of your bunk, having a small, lightweight dry bag for your refuge essentials is a game-changer.

- Earplugs and Eye Mask: These are non-negotiable. In a room of twenty people, someone will snore, and someone will turn on a headtorch at 4:00 AM.

- The Slipper Strategy: While most huts provide clogs, your own lightweight "slipper socks" or flip-flops provide a sense of home and hygiene.

- The Micro-Towel: Refuge showers are tight spaces. A small, high-absorbent travel towel that dries quickly is much better than a bulky traditional one.

- The Bunk-Side Pouch: A small bag to hold your phone, earplugs, and a headtorch (with a red-light mode to avoid blinding others) that you can keep inside your liner.

Final Thoughts: The Spirit of the Trail

The Tour du Mont Blanc is more than just a physical challenge. It is a lesson in adaptability and shared humanity. You will meet people from every corner of the globe, share bread with them, and perhaps even help them find the trail in a patch of fog.The refuges are the stage upon which this drama unfolds. They are not hotels; they are shelters. When you approach them with respect ‒ for the staff who work incredibly hard, for the resources they manage, and for the other hikers sharing your space ‒ the experience is profoundly rewarding. By sorting out your bookings early, carrying enough cash, and embracing the quirks of hut life, you free yourself to focus on what really matters: the sun hitting the granite spires of the Aiguilles Rouges, the taste of a cold beer after a 1,000-metre climb, and the simple joy of putting one foot in front of the other.